Antiphospholipid syndrome is when the body’s defence system goes haywire and makes strange antibodies. These abnormal antibodies cause weird clots to form in our arteries and veins. They usually show up in the legs, but can sneak into other places like the kidneys and lungs too.

Having this syndrome can cause problems during pregnancy, like losing a baby before it’s born or having a baby too early.

Some people call it by different names, like Hughes syndrome or Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome, or even “sticky blood.”

The strange antibodies attack a kind of fat in our bodies called phospholipids. People with this syndrome often have messed-up heart valves, and sometimes young people have strokes because of it.

In the legs, it can make big clots called deep vein thrombosis, which is really bad. And if one of those clots gets stuck in the brain, it could cause a scary thing called a stroke.

There’s no magic cure for this syndrome, but the treatments we have now can really help lower the chance of getting those scary blood clots.

Most people with this syndrome who get treated can live regular, healthy lives. But every once in a while, someone with the syndrome keeps having trouble with clots.

In the United States, between 1 and 5 out of every 100 people might have this syndrome. It’s behind about 15 to 20 out of every 100 cases of deep vein thrombosis or blood clots in the lungs. And it’s more common in women than in men.

Symptoms

The symptoms and signs of antiphospholipid syndrome rely on where the clots go and where they form.

If a clot stays in one place, it can cause:

- DVT: A clot in a big vein, often in the arm or leg, can block blood flow. If it travels to the lungs, it’s called a pulmonary embolism, which is very dangerous.

- Pulmonary embolism (PE): A clot that moves around the body can block blood flow to the lungs, making it hard to breathe.

- Pregnancy problems: It can cause miscarriages, babies being born too early, or hypertension during pregnancy.

Sometimes, less common symptoms can happen, like:

- Migraines or Headaches

- Problems with seizures and memory if a clot stops blood flow to the brain

- A rash that looks like purple lace on the wrists and knees

About 30 out of every 100 people with this syndrome have problems with their heart valves. This can make blood leak back into the heart, causing issues. Some may also have trouble with a heart valve called the aortic valve.

Sometimes, the blood cells called platelets drop, which can lead to bleeding, like nosebleeds or bleeding gums. Some people might see small red spots on their skin from bleeding underneath.

In very rare cases, people might have:

- Involuntary body movements

- Memory problems

- Mental health issues like feeling sad or hearing things

- Trouble hearing

Symptoms usually show up between 20 and 50 years old, but sometimes they start when someone is a child.

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a rare and severe form of the condition, characterized by a sudden and overwhelming formation of blood clots throughout the body. It affects only a small number of people with APS but can cause significant damage to multiple organs. The exact reason why this occurs is not fully understood.

The symptoms of CAPS can vary depending on which organs are affected but may include abdominal pain, confusion, swelling in the feet, ankles, or hands, seizures, progressive difficulty breathing, extreme fatigue, and even coma or death. These symptoms typically emerge suddenly and worsen rapidly, making CAPS a medical emergency.

Immediate intensive care is essential for patients with CAPS to maintain vital bodily functions while receiving high-dose anticoagulant medications. Despite treatment, research indicates that nearly half of patients with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome may not survive the initial episode, and there is a chance of experiencing another episode in the future, even with ongoing medical care. Early recognition and prompt intervention are crucial in managing this life-threatening condition.

Treatment

When someone has antiphospholipid syndrome, a healthcare provider will usually give them medicine to make their blood thinner, which helps stop clots from forming. They’ll likely have to take this medicine for their whole life.

Sometimes, doctors give a mix of different medicines, like aspirin along with Coumadin or warfarin, or sometimes heparin. If one medicine doesn’t work well enough, the doctor might increase the dose or add another medicine.

But these medicines can sometimes make the blood too thin, which can cause bleeding. It’s important for patients to tell their doctor if they notice:

- Blood in their stool, urine, or vomit

- Coughing up blood

- Nosebleeds that won’t stop for more than 10 minutes

- Really bad bruises

If someone with this syndrome gets a clot, they’ll usually have to take heparin and warfarin together. After the clot goes away, they’ll keep taking warfarin.

Treatment During Pregnancy

When a woman has antiphospholipid syndrome and wants to have a baby, it’s important to plan ahead with her doctor even before she gets pregnant. Treatment will begin right at the start of pregnancy and continue until after the baby is born.

If a pregnancy happens unexpectedly, the treatment might not start right away, which could make it less effective.

Usually, the treatment during pregnancy involves taking heparin, aspirin, or sometimes both, depending on if there have been blood clots before or if there were problems in past pregnancies. Warfarin isn’t safe during pregnancy because it can harm the baby.

If the usual treatment doesn’t work well, the doctor might suggest other treatments like intravenous immunoglobulin infusions or corticosteroids.

By the time the third trimester rolls around, if everything seems fine, the doctor might stop the heparin treatment, but the aspirin might still be needed until the baby is born.

Regular blood tests will be needed throughout the pregnancy to make sure the blood is still able to clot properly, just in case the woman gets a cut or a bruise.

Diagnosis

When someone has had a blood clot or lost a baby during pregnancy, the doctor might think it could be antiphospholipid syndrome.

To check, the doctor will do a blood test to see if there are any weird antibodies in the blood.

Sometimes, these antibodies can show up for a short time because of things like an infection or certain medicines. So, the doctor might need to do another test to be sure.

If the blood tests show those strange antibodies, the doctor will look at the person’s medical history to see if the symptoms they’ve had before might be because of antiphospholipid syndrome.

Causes

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) happens because of a mix-up in the body’s defense system, known as the immune system. In APS, the immune system mistakenly produces antibodies that attack the body’s own cells.

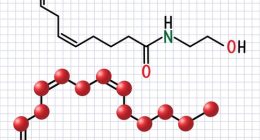

These strange antibodies, called antiphospholipid antibodies, target proteins and fats found in the blood, particularly something called phospholipids. These phospholipids are important for blood clotting, which stops us from bleeding too much when we get hurt.

When these antibodies attack the phospholipids, it makes the blood thicker, which raises the chance of getting blood clots. Normally, the proteins and fats they attack help keep the blood at the right thickness.

People with APS might have antibodies that attack either the phospholipids themselves or the proteins that attach to them.

There are two main types of APS:

- Primary antiphospholipid syndrome: This type shows up on its own without any other health problems.

- Secondary antiphospholipid syndrome: This happens alongside another immune disorder, like lupus.

We’re not exactly sure why autoimmune disorders like APS happen, or why some people with these strange antibodies never have any symptoms. It seems like both genetics and things in the environment might play a role.

Risk Factors

The likelihood of having antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) seems to be influenced by genetics. If someone in the family has the syndrome, others in the family might have a higher risk of getting it too.

There are other things that can increase the risk of APS:

- Having other autoimmune disorders like lupus or Sjogren’s syndrome.

- Infections such as hepatitis C, cytomegalovirus (CMV), syphilis, parvovirus B19, and some others.

- Taking certain medications like hydralazine for high blood pressure or some anti-epileptic drugs.

Sometimes, people have the strange antibodies linked to APS, but they never show any symptoms. However, certain things can trigger the syndrome to show up in these people.

These triggers can include:

- Being overweight

- Being pregnant

- Having high cholesterol or high blood pressure

- Using hormone replacement therapy or birth control pills

- Smoking tobacco

- Sitting still for too long, like on a long flight

- Undergoing surgery

While APS is more common in young and middle-aged women, it can affect anyone, regardless of gender or age.

Prevention

People with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) should take steps to reduce their chance of developing blood clots. This includes:

- Avoiding smoking, as it increases the risk of clotting.

- Maintaining a body weight to reduce strain on the circulatory system.

- Staying physically active, which can help keep the blood flowing smoothly.

Summary

In conclusion, antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a complex autoimmune disorder characterized by abnormal antibodies that increase the risk of blood clots. Diagnosis involves blood tests and assessing medical history, while treatment often includes lifelong medication to prevent clotting. Pregnancy management and careful monitoring are crucial for women with APS.

Understanding the risk factors and triggers, such as genetics, infections, and certain medications, can help individuals take preventive measures. Lifestyle changes, including quitting smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, and staying active, play a vital role in reducing the risk of blood clots in APS. Overall, early diagnosis, proper management, and lifestyle modifications are key in effectively managing APS and minimizing complications.