Achondroplasia is a infrequent genetic condition that makes people shorter and can cause their legs to bow. It happens because of a change in the genes, which tends to occur more often in the children of old aged men.

Dwarfism means being shorter because of genetic or medical reasons. Most cases of dwarfism, almost 90%, happen because of achondroplasia. This condition can run in families, but many people with it don’t have a parent who also has it.

This article talks about the genes behind achondroplasia, including what causes it. It also explains how likely it is to be passed down in families, who’s more likely to have it, and what symptoms it can cause.

What is achondroplasia?

A 2021 review suggested that achondroplasia affects how bones grow, leading to some symptoms like being shorter, having bowed legs, a big head, short fingers, and stiffed elbows. These symptoms can make daily tasks harder, like reaching for things or walking.

People with achondroplasia might also grow lumbar spinal chokes, where uncommon bone growth squeezes the spine nerves, causing weakness and pain. This can seriously affect mobility and is a common cause of later-life disability for them.

They might also have hearing problems and sleep apnea. Unfortunately, people with achondroplasia tend to live about 10 years less than others.

Although there’s no cure, doctors can suggest treatments to help with symptoms. These might include surgeries to fuse the spine, guide bone development, or insert tubes in the ears for hearing problems. These treatments can improve their quality of life and make daily tasks easier.

Reasons for achondroplasia

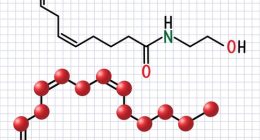

Achondroplasia happens because of a change, called a mutation, in a gene called FGFR3.

Genetic mutations are like little tweaks in our genes that make each person unique. Genes are like instruction manuals for our cells, telling them how to develop, work together, and even when to stop. Sometimes, mutations can change these instructions and cause different traits.

The FGFR3 gene makes a protein called fibroblast growth factor 3 (FGFR3), which helps cells grow, mature, and form bones. When there’s a mutation in the FGFR3 gene, it makes FGFR3 too active, which affects how bones grow.

People with this mutation have bones that don’t grow as much as they should.

Mutations happen naturally and often don’t cause any problems. They can pop up for no proper cause. But some studies suggest that exposure to certain chemicals before birth might raise the chances of having a mutation in the FGFR3 gene. However, more research is needed to confirm this link.

Risks of passing achondroplasia to children

Achondroplasia can inherit since parents pass their genes down to their kids. If someone has a mutation in the FGFR3 gene, there’s a chance they’ll pass it to their child, who might then have achondroplasia.

However, achondroplasia is infrequent. A review from 2020 found that almost 80% of individuals with the state have parents who are of average height. So, these parents are unlikely to have another kid with achondroplasia.

When parents have achondroplasia, the situation becomes more complicated. If couple parents have achondroplasia:

- There’s a 25% chance the child will be average height.

- There’s a 50% chance the child will affect achondroplasia.

- There’s a 25% chance the child will affect homozygous achondroplasia, which is severe and can cause death in infancy.

Impact

Several genetic factors can influence the chances of growing achondroplasia. One important factor is the father age. Research shows that if a father is over 34 years old, there’s a higher chance of their child having the FGFR3 gene mutation that causes achondroplasia, even if the parents don’t have achondroplasia themselves. As fathers get older, the risk increases.

Studies suggest that about 1 out of every 15,000 children will affect achondroplasia. However, when fathers are over 50 years old at the period of their child’s birth, this number increases to about 1 out of 1,875 children. This higher risk is also linked to a group of bone and cartilage conditions, along with achondroplasia, called skeletal dysplasia.

It’s not clear if other factors play a role in the chance of growing achondroplasia.

A review from 2020 found that achondroplasia seems to be more normal in specific bits of the world, like the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, and North Africa. However, the information from these regions isn’t very reliable, so more investigation is needed to understand this better.

Summary

Achondroplasia is infrequent condition where bones don’t grow like they should because of a gene change. This can make things like walking and reaching hard.

Individuals with achondroplasia may pass this gene change to their kids, but not all children of someone with the state will have it.

If a male pare is aged over 35 when his child is born, there’s a higher chance the child might have achondroplasia.